By Khatondi Soita Wepukhulu and Dr Morris P’Lorenga

In the world that Kakwenza Rukirabashaija paints for us, greed has a tone. Greed can be more than just a persistent character flaw. It can be the deeply fallible idea to which much and many (are) is fostered and the author takes you on such a bizarre but likenable fast-paced journey of well-fed greed that as a reader, you arrive at the end of this story with a painful bloated stomach desperately needing release. He mercifully grants it.

Throughout the book, any reader’s stomach will be wound too round, too tight, too unbearable by an alacritous plot of mostly irredeemable characters. The author safely remembers to carry frustration with him, but you’ll start suspecting it is mostly for you the reader, not his characters, and certainly not the story.

The story is busy with more beautiful people than if all our mothers were rounded up, with an insane bildungsroman where coming of age is marked with the powers to turn from human form into a lion or snake. Like, literally.

This book is a testament to how even human complexity is mostly a kinder, vain interpretation of the fact that we’re just the most persistent component of us.

It is proof of a strong stomach because a reader will need it for its irredeemable characters. It will carry a faint question of injelitance but quickly defend itself from it.

The ‘Greedy Barbarian’ will be a tightrope between recalcitrance and merely being a messenger for it.

But mostly, this book will read very familiar indeed, not because you’ve read anything like it, but because it leaves you with the gnawing feeling that it isn’t only the scent of the paper on which this story was written that is lazily finding its way into your real world: it is the feeling that you know primitive acquisitiveness, have been greedy and maybe a barbarian. And if this is how you relate to the book, then who are you?

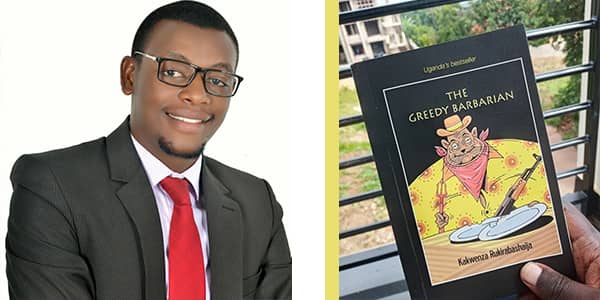

Kakwenza should be a prized budding writer of our time, one whose delicate fire should be blown with the tacit understanding between him and us that he should soon erupt into ablaze.

Inside the Greedy Barbarian

The book is centred around a mischievous man, Kayibanda, whose troublesome characters led him to the pinnacle of power in his adoptive country. From childhood, Kayibanda was driven by stealth, a sense of desolation and yet a drive for self-preservation never seen before. In the end, Kayibanda succeeds using clandestine methods to head one of the most corrupt governments that the world has ever seen.

Kayibanda’s story begins humbly in village called Buregyeya where his grandfather Rukundakanuzire marries a village belle, named Ingabire. The marriage was lucrative, with 30 cows and 10 sheep. The couple go on to live in Buregyeya where they establish themselves to have seven children and grow in wealth comprising many cows.

The birth of the couple’s first-born daughter, Bekunda is what defines the genesis of Kayibanda’s story and later shapes his character. Once Bekunda, the older daughter of Rukundakanuzire became of puberty, many village boys picked interest in her. One day, a respected villager named Bwengye accompanied his son, Baryabusha to propose to Bekunda in marriage. The meeting did not go well. Rukundakanuzire did not approve of the idea of marriage between her daughter and the Bwengye’s.

Rukundakanuzire entered into a fit of violent when Mzee Bwengye insisted on the negotiation. In the midst of his rage, Rukundakanuzire ordered Bekunda’s guests to leave immediately. When Bwengye insisted on persuading Rukundakanuzire to calm down, Rukundakanuzire responded instinctively by piecing Bwengye in the stomach, killing the old man instantly. The seed of bad blood was sown. Bwengye’s sons and entourage fled into the bushes and left the scene. Unfortunately, Rukundakanuzire was also involved in superstitious activities commonly referred to as “night-dancing”. Part of this ritual included flesh-eating (cannibalism), to which Bwengye’s remains was shared before his family could return to claim for it.

The fate of Kayibanda arises from an unfortunate event in the village after the murder of Bwengye. One day, Bekunda was going about her daily chores to collect firewood when four rabbit hunting men pounced on her and gang-raped her. This event changed the life of the family but more profoundly, that of Bekunda, who conceived of the rape. As the tradition dictated, the oldest son of Rukundakanuzire was destined to push Bekunda off the cliff to her death. Any woman who was raped in the village, and who conceived of rape was put to death by throwing off the cliff by the eldest brother. And so, was Bekunda’s fate in the waiting.

Bekunda had to make a choice to flee. Bekunda fled to the City after giving birth to Kayibanda only to find out that for a single mother, life was harder in the city. The city hardship left Bekunda with one choice, to enrol into the trade of the flesh – prostitution. Bekunda was extremely beautiful, spoke less, was humble but lacked skills. Her character attracted many highly valued customers. Her success in this trade became the envy of her colleagues on the streets. That earned her a life-changing beating which left her deformed forever – amputated on one arm with her face deformed. Upon recovery, she was half a human and struggled to speak. She lisped when she spoke.

When Bekunda recovered from her near-death ordeal, she resolved to relocate to a neighbouring country as a means never to cross path with her family. Kayibanda protested, but he was only a little boy. Kayibanda could not imagine where they would go and what awaits them there given the condition of her mother. Would there be a kinder soul? He wondered. On her own, the deformed Bekunda “walked like a scarecrow in a cornfield” with a shuffling gait. When she argued with Kayibanda, Bekunda could quietly struggle to spit a word and could mutter a sentence such as “are you thuwa of what you are theying” (Are you sure of what you are saying?) (pg44).

The trek to the new land began in haste and Bekunda led Kayibanda to the new country where she met a pastoralist wanderer Kagurutsi at the confluence of R. Mahurunguru that divided the two countries.

Kagurutsi was a modest man who had lost both his wife and child. He lived alone in his village attending to his cows. Kagurutsi was a generous man who took in Bekunda and Kayibanda and provided for them for over two months while Bekunda recovered. As time went by, Bekunda was no longer in a rush, she had become comfortable and comforted with the security that Kagurutsi provided them. Kagurutsi prided himself of his Chwezi roots and created an illusion around some mysticism that he could transform himself into any animal and revert to his human forms again. At least, that was his reputation in that village.

One day, Kagurutsi noticed that Bekunda had become lively, firm and the milk had healed her physically and spiritually. The beauty that was hidden in her insecurities had started blossoming into a full figure. Kagurutsi felt the tingle of affection whenever he was in close proximity to the half-dame. Kagurutsi was becoming a responsive man to a wonderful female. Later that month, Kagurutsi asked Bekunda for her love and they got married. Kayibanda was in agreement because Kagurutsi had loved him so much as his own son. Kagurutsi had taught Kayibanda all the skills and tricks of cattle keeping and had placed Kayibanda into the neighbouring school to learn discipline formally.

Kagurutsi and Bekunda went on to have two other children one named Kanyeigabo. However, Kayibanda became more of a destructive loner and too troublesome as he became of age. His anti-social behaviours became prominent as he fought everyone at school, burnt huts in the villages and terrorized the village boys when angry. One thing, Kayibanda was also a prolific liar who never admitted to any of his transgressions in the villages. The villagers were growing increasingly weary and had plans to raid Kagurutsi’s home to avenge the mishaps of Kayibanda. One day, Kayibanda sneaked out of his hut to go set a hut of a village fellow he had disagreed with. The villagers had expected his wrath to lead him to such. As fate was, Kagurutsi had suspected that his son was up to no good that day. So Kagurutsi kept watch over him and waited until Kayibanda left his hut in the thick of darkness and then followed Kayibanda. Apparently, Kagurutsi turned into a snake and slithered fast behind Kayibanda on his mischief mission. When Kayibanda was about to set the huts in the next village on fire, the villages ambushed him and beat the hell out of Kayibanda. They tied Kayibanda with a rope and dumped him to drown in the river.

The snake slithered to the River and transformed into Kagurutsi – the human being to rescue his troubled son from drowning. The two returned home without uttering a word to each other. Kayibanda requested Kagurutsi not to say a word about this ordeal to Bekunda. This incident, however, forced Kagurutsi to send Kayibanda away to his uncle Bamwine in another town where Kayibanda could be schooled.

The second chapter, the character of Kayibanda takes centre stage and is developed more. Kayibanda settles in the home of Mr Bamwine and begins regular school. However, his character becomes more prominent as a troublemaker, a notorious bandit, a ferocious thief, unconscionable criminal – a curmudgeon. Kayibanda was simply impossible, an inventor of trouble, a hypocrite with a bad demeanour, a soar loser, a bully, and so forth. Mr Bamwine put Kayibanda in a good school in Mpara where Kayibanda’s performance was episodical. He occasionally did well when not causing trouble and performed poorly during his troublesome episodes peaked. Fortunately, Kayibanda succeeded in his advanced level school certificate examination to qualify for a scholarship abroad.

The third chapter explores Kayibanda’s life at the university where his deceptive and joy-killing character developed further. The troubles that Kayibanda experienced in building relations with his peers that he led to troubles. The Chapters are quite long and invite excessive patience for the reader. This last chapter describes Kayibanda’s strives to organize himself as a notorious leader of a political group and later military group that exploited young children (Kadogo’s). It narrates in haste Kayibanda’s struggles with the family and a controversial decision to marry Chief Bam wine’s daughter. His incursion into the new political environment where he participates in killing a Chief justice of that country as well as overthrowing a regime to establish his own government – the most corrupt, sectarian, murderous, deceptive, and dangerous regime of its kind. Under Kayibanda’s regime of terror, everything was lacking to the people and the yet Kayibanda established a system of governance that muzzled the voices of the people.

Overall, when you read the book, every scene sounds like a familiar story that you already know but without confirmation. Some of the scenes are surreal, while others appear drawn from an insider knowledge or whispers from the power corridors. It looked like the author muzzled courage to place these myths and street talks into a novel of a sort. The book could have been done better had the chapters been shorter to allow for sufficient space and depth to developing the characters and scenes in finer detail. Overall, this book is worth reading as fiction and yet a contemptible fiction that, without doubt, could have been the sole reason that the author was jailed.

It has the potential to make the current authority in Uganda nervous, and rightfully so!